At an FA Cup semi-final hosted at Hillsborough Stadium in Sheffield, more supporters than could be safely accommodated were allowed to enter the Leppings Lane End of the ground without satisfactory police monitoring.

A crush ensued, resulting in people being pressing up against each other as well as the fencing that stopped them from getting access to the pitch. Legs, arms and ribs were all broken in the horrifying crush, yet after the fact those that ran Sheffield Wednesday Football Club refused to admit that there was a problem or take any blame.

That incident occurred when Tottenham Hotspur played Wolverhampton Wanderers in 1981, a full eight years before the fateful day on the 15th of April 1989 when 96 football fans would lose their lives in the worst sporting disaster ever to occur on British soil.

It was at a match between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest and the response of Sheffield Wednesday to the events of eight years previously saw them alter the design of the Leppings Lane End of the stadium, thereby invalidating their safety certificate. Here we’ll explore the build-up to the disaster as well as the reasons for it and the aftermath. Though we will be as balanced as possible, we will not pull our punches.

The Build-Up

The Football Association had long employed a method of using neutral venues to host the semi-final phase of the FA Cup, with Hillsborough Stadium having been on their list for years. After the 1981 crush it was removed from the list of options until 1987, with numerous changes to the ground occurring during that time. For starters the Leppings Lane End was no longer one big concourse, instead being split up firstly into three pens and then into five. in 1986 a decision was taken to remove a crush barrier from the access tunnel in order to allow fans to enter the pens more efficiently.

When the ground was finally allowed to host big matches again in 1987 there were still reports of over-crowding, with Leeds fans describing the complete lack of organisation at their semi-final match against Coventry City. They pointed to a lack of policing within the stadium, as well as no direction being given to supporters by the stewards inside the ground. Liverpool themselves played against Nottingham Forest there in 1988 and fans complained of crushing. The club lodged an official complaint with the FA when the same stadium was chosen for the 1989 semi-final.

Though there had been issues in previous years the matches had at least been overseen by a competent match commander in Chief Superintendent Brian L. Mole. However a prank within his division committed in October 1988 saw numerous officers disciplined and Mole moved to Barnsley from the 27th of March 1989. That meant that an inexperienced, newly promoted officer by the name of Chief Superintendent David Duckenfield was asked to take over as match commander for the game between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest.

It is quite usual to segregate football supporters at matches and has been for a long time. Liverpool Football Club never objected to this, however they did ask the Football Association to change round the allocation of stands from the previous year. Liverpool FC typically take more fans to matches than other clubs and the South Stand and Spion Kop could also take just shy of 30,000 supporters, rather than the 24,256 that could fit in the North and West Stands. The request was denied and the Forest supporters could therefore enter through 60 different turnstiles whilst the Liverpool fans had access to the ground via 23 turnstiles.

A combination of factors meant that Liverpool supporters were arriving at the ground slightly later than the police would have liked, though still with plenty of time to enter the stadium had it been properly marshalled. In 1988 three different trains ran from the city of Liverpool to Sheffield, whilst in 1989 this was reduced to just a single train. On top of that there were roadworks on the M62 that caused a slight delay in traffic getting into the city. This resulted in fans trying to get into the stadium but unable to as there weren’t enough turnstiles to cope with them or officers to direct them where to go.

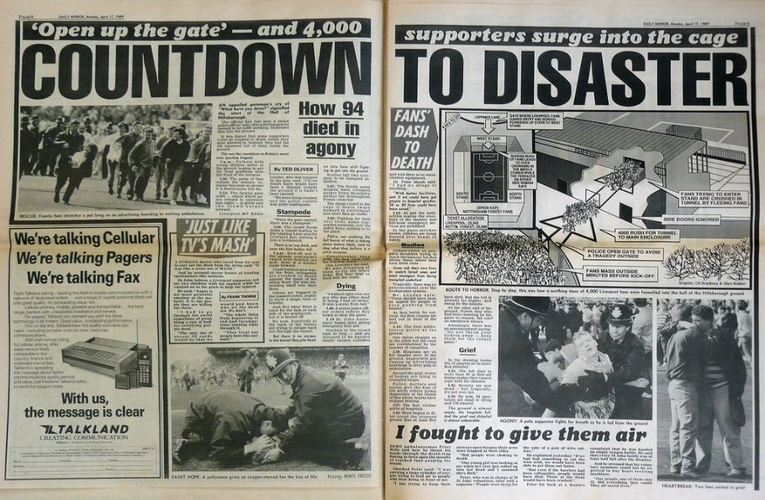

A constable who was in amongst the crowd radioed through and asked for the game to be delayed. This had happened in 1987 in order to get all of the fans inside the ground safely, but his request was denied. Police outside the stadium were concerned at the build-up of fans and asked for Exit Gate C to be opened in order to avoid fatalities. The match commander gave permission for this to happen, with Exit Gates A and B also being opened a little later.

The Disaster

As people began to enter the stadium they will have seen an entrance into the Leppings Lane End of the ground in front of them. This led to Pens 3 and 4, with side passages taking people down to the other pens. These side entrances weren’t obvious, however, and in previous years supporters had been directed into them by the police and stewards. No such direction was offered in 1989, resulting in more and more supporters entering the already full central pens and putting pressure on supporters at the front. The police believed that supporters would ‘find their own level’ and left them to it.

The problem with this approach was that there was fencing at the front of the pen that stopped people from getting onto the pitch and similar fencing stopped them from moving sideways into the less crowded pens. A shot at goal from Peter Beardsley that hit the crossbar at 3.05pm caused the fans inside the pens to surge forward in excitement. There were metal crush barriers throughout the pens designed to stop people from getting hurt, however the sheer volume of people in the pens caused one of them to give way and people were forced forward on top of each other as well as into the fence right at the front.

Supporters within the pens were shouting to the police to tell them what was happening and asking them to help. Some fans were trying to climb the fence or were being lifted up onto the upper tier by those above who could see what was happening. Elsewhere in the ground people had no idea what was happening and the police at first thought it was an attempted pitch invasion, therefore they pushed supporters back into the crush. It wasn’t until 3.06pm that the ground commander, Police Superintendent Greenwood, realised what was happening and ran onto the pitch to tell the referee to stop the match.

Even as holes were being ripped into the fence at the front of the pens and fans were spilling out onto the pitch, police officers were forming a cordon across the field of play. They still believed that it was a pitch invasion and were put in place to stop the Liverpool supporters from reaching the Nottingham Forest fans on the other side of the ground. Meanwhile some uninjured Liverpool fans were tearing down advertising hoardings to use as makeshift stretchers in order to take the injured and dying to ambulances that were still outside of the ground. Others administered CPR where possible.

Incredibly a total of 44 ambulances arrived at the stadium once a major incident alert had been sent out, but only one was allowed to enter the stadium. The police prevented the others from driving onto the pitch and consequently just 14 of the 96 victims of the disaster made it to a hospital. 94 people died on the day, with the youngest victim being just ten-years-old and the oldest 67. Four days later a fourteen-year-old named Lee Nicol passed away when his life support machine was turned off. In 1993 the 96th victim’s life was claimed when Tony Bland, who had been in a vegetative state for the four years since the disaster, had his artificial feeding and hydration withdrawn.

The Aftermath

As well as the 96 people who lost their lives as a result of the disaster there were also 766 serious injuries. The true toll of the disaster is far more difficult to calculate, with several people committing suicide in the years after as a result of survivor’s guilt.

In the wake of the disaster a decision was taken to launch an inquiry as to what had happened, led by Lord Justice Taylor. The Taylor Report completely exonerated the Liverpool supporters from any blame and declared that ‘the main reason for the disaster was the failure of police control’. Unfortunately the report did little to quell the notion that Liverpool fans were to blame, with the tabloid newspaper The Sun printing a front page a few days after the disaster that claimed to be reporting ‘The Truth’, telling lies about how Liverpool fans stole from the dead, abused police officers and urinated on them. A boycott of the newspaper exists on Merseyside to this day.

In spite of the fact that this was proven to be a complete nonsense, the story stuck. It was part of an attempted cover-up by members of South Yorkshire Police, who also began to weave a narrative that Liverpool supporters had turned up late to the ground and were drunk. The force went around the stadium the day after the disaster taking photos of the bins around the ground to ‘prove’ that they were full of beer cans. In reality there were mostly pop bottles seen in the photographs and local publicans admitted that fans were drinking ‘no more than usual’.

Incredibly, the attempts to shift the blame for the disaster away from the authorities saw alcohol level blood samples taken from the victims, including a ten-year-old boy. The original inquest into the disaster, which was then the longest in British history, concluded that all deaths were accidental. This caused uproar with the families of the victims who wanted people to be held accountable for the loss of their loved ones. Some even refused to pick up the death certificates, unwilling to have a piece of paper that said their child had died accidentally when they believed it was anything but.

The Hillsborough Independent Panel

The families tried on numerous occasions to get the case re-opened, with the ‘Fight For Justice’ lasting for decades. Even when new evidence was found, such as for the 1996 TV documentary Hillsborough by Jimmy McGovern, Lord Justice Stuart-Smith decided it wasn’t enough to justify a new inquiry.

It wasn’t until the Hillsborough Independent Panel was formed in 2009 to investigate the disaster and review any new evidence that a change in the wind came about. It released its findings in 2012 and revealed the extend to which the police had attempted to cover things up and shift the blame onto supporters. That included the altering of 164 witness statements, with 116 of them changed to remove negative comments regarding the South Yorkshire Police. The Panel also found that up to 41 of those who died could have been saved had the emergency response been better.

The Panel’s findings resulted in an official apology to the families of the victims and Liverpool supporters from the then Prime Minister, David Cameron, and the leader of the opposition, Ed Milliband. It also led to a new inquest being held into the disaster, led by Lord Justice Goldring. This became the longest inquest in British legal history, surpassing even the original inquest into Hillsborough. At the end of it a verdict of ‘Unlawful Killing’ was returned on all 96 victims of the disaster.

Liverpool Football Club added flames to either side of their crest in memory of the fans after the disaster and a memorial stands at both Hillsborough and Anfield, dedicated to the memory of the 96 supporters who lost their lives as a result of police negligence and incompetence. Though this section of the site has barely scraped the surface of what happened on the 15th of April or in the years that followed, we hope we have given you the beginnings of an understanding into the disaster and the subsequent cover-up.