It is a curious and saddening quirk of fate that Liverpool Football Club has been involved in two of the worst sporting disasters in history.

It is also a depressing fact that when football fans ask for ‘justice for the 96’ the response from some quarters is “What about justice for the victims of Heysel?”, as though a tit-for-tat argument over people who lost their lives is a perfectly valid response to things. It’s not, of course, and victims of disasters, whatever the cause, shouldn’t be used to try to score points over rival fans.

Four years before the Hillsborough Disaster would rip through communities across Liverpool, the Reds made it to the final of the European Cup were they were due to face Juventus.

Here we’ll give you an outline of the disaster that took the lives of 39 people when a group of supporters in the Liverpool end of the stadium rushed at a wall, which collapsed. The disaster resulted in repercussions not just for Liverpool Football Club but for the English game itself.

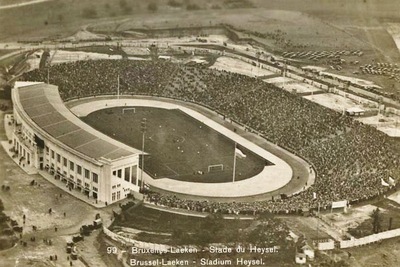

Heysel Stadium

Even though it was the national stadium of Belgium, Heysel was a decrepit stadium in desperate need of repair by 1985. It was over 50-years-old and had not been well-maintained, with numerous parts of the stadium quite literally crumbling apart. The outside wall of the ground was made of a cinder block material that meant that fans without tickets could actually just kick holes in the wall to get inside.

Even though it was the national stadium of Belgium, Heysel was a decrepit stadium in desperate need of repair by 1985. It was over 50-years-old and had not been well-maintained, with numerous parts of the stadium quite literally crumbling apart. The outside wall of the ground was made of a cinder block material that meant that fans without tickets could actually just kick holes in the wall to get inside.

None of this was unknown to anyone, with Arsenal having described the ground as ‘a dump’ when they played there a few years before. Both Juventus’ President Giampiero Boniperti and the Liverpool CEO Peter Robinson wrote to UEFA and pleaded with them to pick another venue, such as the Nou Camp in Barcelona or the Bernabéu in Madrid. Despite the warnings and the fact that the final would feature two of the best supported teams in Europe, UEFA declined the opportunity to host it somewhere else.

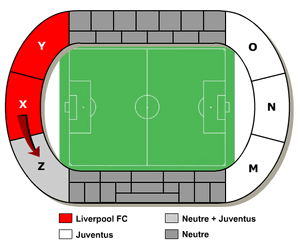

Another decision taken by UEFA that both clubs objected to was the choice to have a ‘neutral’ section in the ground. Tickets for section Z were reserved for Belgian fans with allegiance to neither team, though predictably enough these were sold by touts outside the ground allowing fans from both teams to mix in a dangerous atmosphere. Despite the fact that Juventus were given sections O, N and M and Liverpool were only given X and Y, most of the tickets ended up being bought by Italian fans and a small number of supporters from Merseyside.

The Disaster

At about 7pm Belgian time, trouble began to fester. Liverpool supporters in section X and Juventus fans in section Z were separated by an entirely inadequate and temporary chain-link fence. The area was also lacking in a police presence, meaning that people from both sides were able to provoke each other by throwing rocks and stones from the crumbling walls across the boundary.

As kick-off neared this throwing of stones grew worse. They were mainly being thrown from the Juventus section, meaning that supporters in the Liverpool end grew increasingly angry. Soon they decided to try to put a stop to the stone throwing and so they charged through the area separating the two sets of fans and over-powered police. The Juventus fans fled from the scene and towards a wall at the perimeter of section Z.

The poor nature of the ground meant that the wall could not take the force of so many fans and it soon collapsed. It was not actually the collapsing of the wall that caused 39 people to lose their lives. Instead its collapse relieved the pressure and the victims were killed by suffocation. There were also more than 600 fans who were injured in the incident.

The bodies were laid out on the side of the pitch and covered with football flags. Unfortunately a medical helicopter flew in and blew off the coverings, revealing the bodies for all in the ground to see. The Juventus supporters at the opposite end of the ground began to riot when they understood what had happened, attempting to advance on Liverpool’s end only to be stopped by the police. They fought, with some fans attacking the Belgian officers with rocks, stone and bottles.

Incredibly, a decision was made to allow the match to take place regardless. It was felt by UEFA officials as well as the Belgian Prime Minister and Brussels Mayor that abandoning the match could lead to more violence outside the stadium. Juventus went on to win the game 1-0.

The Aftermath

Though Liverpool fans bore the sole blame for the disaster in its immediate aftermath, an investigation into events led several top officials as well as the Belgian police captain Johan Mahieu to also shoulder some responsibility. In April 1989 fourteen Liverpool fans were convinced of manslaughter, as was the Belgian police chief.

Back in England a response was required from the government. Margaret Thatcher, who was Prime Minister at the time, suggested that English clubs should be withdrawn from European competitions. It was a useless gesture in the end, with UEFA banning all English clubs ‘for an indeterminate period of time’ just two days after Thatcher’s request. In 1990 English clubs were allowed to re-enter European competitions, with the exception of Liverpool who remained banned for a further year.

In the wake of Heysel English clubs attempted to be stricter with the sort of people who were allowed entry to their stadiums, including the introduction of a ban for troublemakers for three months. Ludicrously, Heysel continued to be used as a stadium for the best part of a decade, though no football matches were held there again until after it was re-built as the King Baudouin Stadium in 1994.

Both clubs struggled to deal with the disaster for many years afterwards. It wasn’t until 2010 that Liverpool Football Club unveiled a permanent plaque to the victims of the disaster on The Centenary Stand at Anfield. A Heysel Memorial was installed at Juventus’ J-Museum in Turin in May 2012.