We all take football very seriously indeed. A club’s transfer activity can have us all rushing to our keyboards to express our disappointment or, worse, taking to the street in protest.

Bill Shankly’s well-known phrase, ‘Some people say football’s a matter of life and death. I’m very disappointed by that attitude. It’s much more important than that’ is used as much as a motto as a witticism.

Ultimately, though, football is a game and the following of it is a hobby. It should never be the case that anyone goes to see a game but doesn’t get to come home afterwards. That is the ultimate tragedy and something that shouldn’t ever happen.

Sadly, though, from time to time it does happen. In 1946 it happened at Burnden Park when 33 people were crushed to death. Here is what happened on that fateful day.

Build-Up To The Disaster

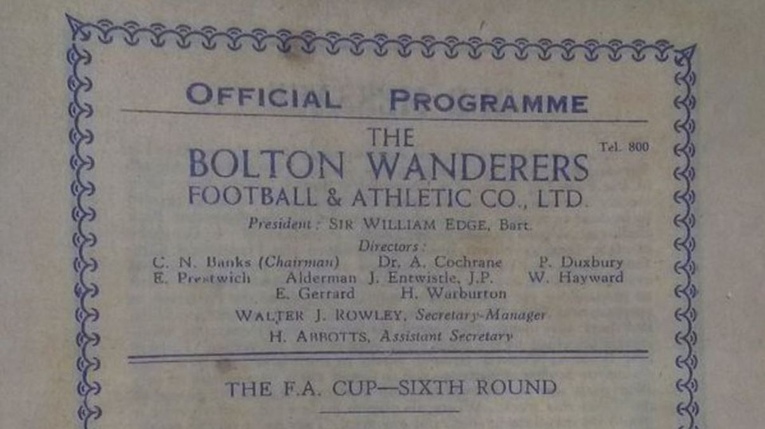

It was the ninth of March 1946 and Stoke City were the visitors at Bolton Wanderers then home Burnden Park. It was the second-leg of the sixth round tie between the two teams with a place in the semi-finals of the world’s oldest cup competition up for grabs. Bolton fans were confident, having seen their side beat Stoke 2-0 at the Victoria Ground the week before.

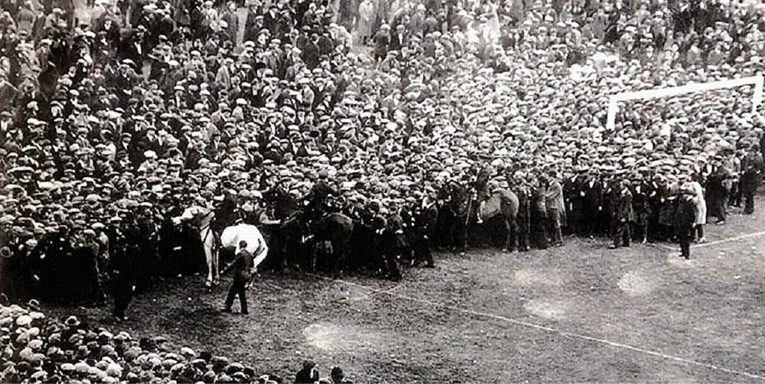

The situation was compounded by the fact that more people than expected turned up at the stadium to watch the game. This was the first season proper since the end of the Second World War and supporters were desperate to get back to the escapism of live football. They were also excited to see one of the game’s greats line-up for Stoke, Sir Stanley Matthews. More than 85,000 people made their way into the ground on that fateful day.

Part of Burnden Park had been requisitioned by the army and consequently some of the stand at the Burnden end of the ground was closed to supporters. That meant that fans from both clubs who were watching from either end of the ground had to enter via the same turnstiles, whilst other supporters also had to pass through that area on the way to a different terrace section, creating something of a bottleneck. This was also made worse further by the fact that the turnstiles at the Railway Embankment hadn’t been in operation since 1940.

As was the nature of things at the time, supporters didn’t buy their tickets in advance and tended to buy them on the turnstiles beforehand. All of this led to one end of the ground becoming over-crowded. As a result it was decided at 2.40pm that the turnstiles should be shut and no more supporters should be allowed to enter the stadium.

Sadly the closing of the turnstiles did not do enough to deter supporters from entering the ground. They climbed over the turnstiles, climbed in from the nearby railway line and came in through a gate which was unlocked and opened. Many fans ended up being pushed along the side of the pitch to the far end of the ground and eventually outside of it into the car park.

The Crush

Not long after the game had kicked off people started spilling onto the pitch. The match was temporarily halted whilst they were cleared from the playing surface. It was at this moment that two crash barriers collapsed. The crowd behind the barriers pushed forward, unaware that there were people underneath the barriers who were then crushed. A crowd rushed onto the pitch from the Embankment End and crushed people underfoot.

The game kicked off again but then a police officer came onto the pitch and told the match referee what had happened. George Dutton, the ref, called the two captains into the centre circle and informed them that there had been a fatality. Harry Hubbick, the Bolton captain, and Stoke’s captain Neil Franklin then led their players off the pitch.

Those that had perished in the accident in the Railway End terrace were laid down along the touchline. Coats were placed over their bodies where available out of respect. Incredibly the game was back underway within half an hour. As some of the bodies were encroaching the pitch a new line was made out of sawdust to separate them from the players. When the first-half came to a conclusion the players didn’t leave the pitch as usual for half-time but instead simply changed ends and kicked off again.

Simon Marland is a club historian from Bolton and he believes that the decision to continue playing was down to communication problems. He said, “If you were stood on the other side of the ground and you saw people lying on the pitch you’re probably thinking they’ve fainted. You wouldn’t dream of people dying at a football match”.

Stanley Matthews later wrote that he had no idea how many people had passed away and that he felt sick when he found out. He later donated money to a charity set-up for the victims of the tragedy. Marland believed that, as much as Matthews might have been disgusted that the game had carried on it was probably the right thing to do. He felt that the inability to communicate with the crowd meant more unrest might have followed if the match had simply been abandoned.

The Aftermath

33 people died during the disaster with hundreds more Bolton fans severely injured. It was the worst stadium disaster in British history at the time, later surpassed firstly by the Ibrox Disaster in 1971 and then by Hillsborough in 1989.

A report into the disaster was commissioned and run by Moelwyn Hughes. It recommended that teams should gain a more rigorous control of crowd sizes at games. It was suggested that a voluntary code be put in place with local authorities inspecting grounds with capacities of 10,000 and that safety limits be put in place at grounds of more than 25,000. It was also said that turnstiles should be able to record spectators coming into the grounds mechanically and that all stadiums should have internal telephone systems.

The Burnden Park Stadium Disaster is seen as the forgotten disaster in British football. 33 people lost their lives and that is something that should never be forgotten.