One of the most fascinating things about football, away from the matches themselves of course, are the number of things involved in the game that we seemingly take for granted. We know that a referee uses their whistle to start the match, but few people who listen to the sound on a weekly basis would be able to tell you when it was first used or why. We’ve written elsewhere on this site about the corner flag, which has a far more interesting history than you would ever have imagined. Another example of this notion of taking important aspects of the game for granted comes in the form of the goals and goalposts.

Few items on the football pitch other than the ball itself are quite as important as the goals, which are the centre of attention for both of the teams playing the game. Whether they’re attempting to score in the opposition’s goal or protect their own, footballers have the post and the crossbar lodged firmly in their mind from the moment the match gets underway. As fans of the game, most of us could draw a set of goalposts, complete with the crossbar and net, but how many of us know when they’ve been part of football since? Were they there on the first day that a ball was kicked in anger, or are they a relatively modern thing? Has their design changed at all? We’ll tell you what we know here.

The First Use Of A ‘Goal’

If you’ve read our piece on the history of football itself then you’ll know that a version of the sport can be traced back to the day of the Chinese Emperor Ch’eng Ti, who ruled in around 32 B.C. The first known reference to a goal came in his time, when two bamboo sticks stood with a net made of silk stretched out between them.

If you’ve read our piece on the history of football itself then you’ll know that a version of the sport can be traced back to the day of the Chinese Emperor Ch’eng Ti, who ruled in around 32 B.C. The first known reference to a goal came in his time, when two bamboo sticks stood with a net made of silk stretched out between them.

In England it’s believed that the first use of something akin to a goal came in 1681 when the King’s servants played against those of the Duke of Albermale and the doorways of two forts were the objects of their ambition. Indeed, during the seventeenth century a ‘goal’ was considered to be the space between two fixed objects, regardless of how far apart they were.

Of course, none of those examples are relevant to the actual sport of football. That didn’t come about until the middle of the 1800s, with similar sports having been played before then but the one that we know and love today going through numerous rule changes before the ones that we play now came into being. In 1801, for example, Joseph Strutt said that a goal consisted of ‘two stick driven into the ground’, whilst the Uppington School rules said that a goal was scored when the ball went through ‘the goal and under the bar’.

The first version of rules that football tends to look towards was written in 1848 with the production of the Cambridge rules, which declared a goal to be scored when the ball goes ‘through the flag-posts and under the string’; the clear implication being that a crossbar wasn’t yet thought of. The Eton rules were a tad more specific, saying that the ‘goal-sticks’ should be ‘seven feet out the ground’ with the space between them ‘eleven feet’, with the ball needing to go between them but ‘not above’ for it to be valid.

The Football Association’s Rules

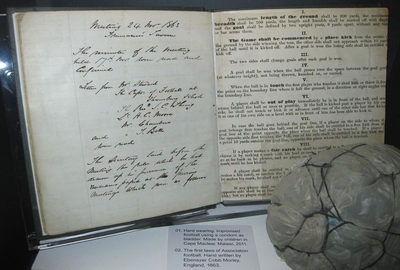

The first codified version of the rules as laid out by the Football Association were written down in 1863.

Though countless of these rules have changed over the years, from the job of the referee through to what penalties should be awarded for and whether or not goalkeepers are allowed to pick up the ball, the FA’s initial ruling on the distance between goalposts has remained the same ever since.

The 1863 rules stated that goalposts should be eight yards apart. The one thing that wasn’t mentioned back then, however, was a crossbar. In fact, the 1863 version of the Laws of the Game didn’t say anything about such a thing, whether it be made of tape or rope.

Some clubs still chose to use string to make a crossbar, with those that didn’t finding that the opposition would claim for a goal even if the ball was thirty yards higher than the posts.

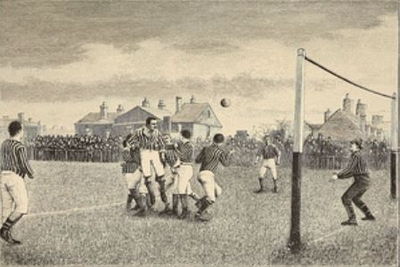

The Crossbar

The result of the ridiculousness of such goals being argued over resulting in the Football Association amending their rules in 1866, adding that the use of tape between the two posts was required from then on. Tape was used in the first ever FA Cup final in 1872, resulting in clubs accepting that the crossbar was not to be just a passing fad. As a result, the likes of Sheffield Football Club and Queens Park both installed them, with each claiming to be the first club in the world to do so. The crossbar became a mandatory addition to the goal ten years after the first FA Cup final when the rules were amended again in 1882.

The result of the ridiculousness of such goals being argued over resulting in the Football Association amending their rules in 1866, adding that the use of tape between the two posts was required from then on. Tape was used in the first ever FA Cup final in 1872, resulting in clubs accepting that the crossbar was not to be just a passing fad. As a result, the likes of Sheffield Football Club and Queens Park both installed them, with each claiming to be the first club in the world to do so. The crossbar became a mandatory addition to the goal ten years after the first FA Cup final when the rules were amended again in 1882.

Even when the necessity for a crossbar became a mandatory requirement, clubs still struggled to figure out how to make it work. In 1888, for example, the London team Kensington Swifts found itself disqualified from the FA Cup because one of its crossbars was lower than the other, resulting in a complaint from Crewe Alexandria. Was that a deliberate tactic, or simply a problem with construction of the goals? The latter was likely to be the result of the crossbar breaking in 1896 when the Sheffield United goalkeeper William Foulkes swung off his crossbar; though the fact that his nickname was ‘Fatty’ means that’s open to some debate.

Nets As ‘Huge Pockets’

As with the crossbar, there was nothing about goal nets in the original 1863 FA Rules of the Game. Nothing was introduced about them in 1866 nor in 1882 when the rules were amended, but as football became more and more popular rows tended to be more and more commonplace regarding whether or not the ball had actually been scored.

As with the crossbar, there was nothing about goal nets in the original 1863 FA Rules of the Game. Nothing was introduced about them in 1866 nor in 1882 when the rules were amended, but as football became more and more popular rows tended to be more and more commonplace regarding whether or not the ball had actually been scored.

In the 1880s Ireland argued that an England goal shouldn’t have stood because they believed that it had gone over the bar rather than under it. The fact that it was the final goal in a 9-1 defeat didn’t matter to the Irish, who wanted the score to at least be fair and accurate. Ironically, four years later and England argued that Ireland’s goal shouldn’t have stood in a far more respectable 2-2 draw because they felt it had gone wide of the post.

In the end it was a Liverpudlian engineer that came up with the solution to all of the arguments and fallings out. John Brodie had large pockets on his trousers and realised that if goals had similar such ‘pockets’ then the ball would nestle into them if they were legitimate. He completed his new ‘pockets’ in 1891 and trialled them during a game in Nottingham. Within the year the Football Association accepted them and added them into the Rules of the Game, with the new item being used in the FA Cup final of 1892.

Brodie’s invention might well have reduced the number of arguments but the new goal nets certainly didn’t end them. In 1909, for example, the ball hit the net but bounced back out, resulting in the match referee saying no goal had been scored and West Brom missing out on promotion as a result. The same thing happened in 1970, leading to the Baggies’ fellow West Midlands side Aston Villa being relegated when a valid goal wasn’t given.

One of the most controversial goals in the history of football came in 1966, of course, when Geoff Hurst’s shot hit the crossbar and bounced down, with the Russian linesman declaring it to be a goal. Was it one? Who knows. The result, however, was that England won the World Cup for the first time and the ball didn’t even need to hit John Brodie’s invention for it to count.

The Shape Of The Posts

The final thing worth mentioning is the shape of the posts themselves. Once the FA had introduced them as a necessity, they were actually square. This remained the case until relatively recently, with FIFA only banning square posts in 1987.

The final thing worth mentioning is the shape of the posts themselves. Once the FA had introduced them as a necessity, they were actually square. This remained the case until relatively recently, with FIFA only banning square posts in 1987.

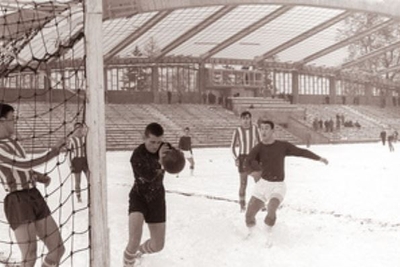

That decision to enforce the use of more spherical posts was as a result of controversy during the European Cup final between Bayern Munich and Saint Etienne at Hampden Park. The Scottish ground was still using square goal frames at the time, which Saint Etienne later blamed for their loss as they struck the crossbar twice in a manner that might have resulted in a goal if today’s round frames had been in use. In the wake of the match the French press dubbed the goal frame at Hampden Park ‘les poteaux carrés’, or ‘the square posts’. Bayern won the game 1-0.

Nowadays goals are made out of steel sections of aluminium that meet strict safety criteria. The problem of whether or not the ball has crossed the line, as witnessed most famously in 1966, has been eradicated in the top level of the game thanks to the introduction of goal line technology. What changes might occur in the future?