On the 14th of February 2005 Arsenal welcomed Crystal Palace to their old ground Highbury for a Premier League game. In Arsene Wenger’s squad there were six French players, three Spanish lads and two Dutch players. There were members of the team from Germany, Cameroon, the Ivory Coast, Brazil and Switzerland. The most noteworthy thing, however, was that there were no English players in his squad whatsoever.

On the 14th of February 2005 Arsenal welcomed Crystal Palace to their old ground Highbury for a Premier League game. In Arsene Wenger’s squad there were six French players, three Spanish lads and two Dutch players. There were members of the team from Germany, Cameroon, the Ivory Coast, Brazil and Switzerland. The most noteworthy thing, however, was that there were no English players in his squad whatsoever.

It was a watershed moment for English football, the first time an entire squad contained not one player from England. There had been a similar incident a full seven years before when Gianluca Vialli sent out his Chelsea side to play against Southampton with no English players in the starting eleven, but both Jon Harley and Jody Morris appeared for the Blues towards the end of the game meaning that at least two English players had played for the club that day.

Yet what was all the fuss about? As much as the press and managers might like to claim that foreign players have hampered the development of the England national side, is there any truth to that? How long have foreign players been plying their trade in this country?

The First Foreign Players

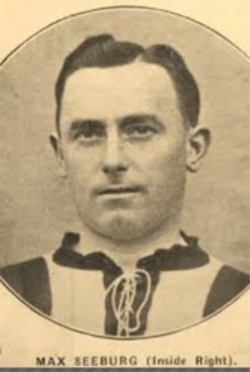

Many critics of the influx of foreign players into the English game tend to blame the decision by what was essentially the EU in 1978 to force England to allow European nationals to play over here, but that’s a bit of a false argument. For starters, the first non-British player to run out for an English club was Max Seeburg, playing for Tottenham in the 1908-1909 season.

Many critics of the influx of foreign players into the English game tend to blame the decision by what was essentially the EU in 1978 to force England to allow European nationals to play over here, but that’s a bit of a false argument. For starters, the first non-British player to run out for an English club was Max Seeburg, playing for Tottenham in the 1908-1909 season.

Seeburg was born in Leipzig, Germany and actually signed for Chelsea in 1906. He never made a professional appearance for the West London club, however, and moved across to Spurs for the start of the 1908-1909 season. He actually only made one appearance for Tottenham – a 1-0 loss away to Hull City before moving on, eventually ending up at Grimsby Town FC amongst others. Still, the spell of no foreign footballers was actually broken a full seventy years before the EU made any demands at all on the English game.

Another thing that needs to be considered is the fact that Scottish, Welsh and Irish footballers regularly ran out for English club sides in the early days of the game (and ever since). Of course none of them are ‘foreign’ as they were all members of the United Kingdom, but they weren’t English. Some of the English game’s most famous faces, from Bill Shankly through to Alex Ferguson via Kenny Dalglish and George Graham, have come from North of the Border.

If you want to get really picky then you might want to look up the name of Walter Bowman, the first person from oversees to play for a Football League team. He ran out for Accrington Stanley in 1892 and had been born and raised in Canada as well as having Swiss heritage. Three years after Max Seeburg played for Spurs an African international named Hussein Hegazi played for Fulham, so the idea that foreign players plying their trade in the league is a relatively new thing is clearly a nonsense.

In 1931 the Football Association decided to take something of a hard stance on the foreign footballer issue. They introduced a rule that required players to have been resident in the United Kingdom for two years before they would be able to play for an English club. That didn’t stop a German player named Bert Trautmann winning the Football of the Year Award in 1956, but it did temporarily put a halt on non-British players playing in the English league.

The requirement for players to have lived in the UK for two years before playing for an English side lasted for 47 years. Two Danes, however, did play in the best division of the league during the late 1940’s: Karl Aage Hansen (Huddersfield) and Viggo Jensen (Hull City). Both were members of the Danish national team which beat Great Britain 5-3 in the bronze match of the Olympics in 1948.

It’s difficult to know how long the FA would have been able to stop clubs bringing talented players from abroad into the English leagues had they wanted to, but the point was moot after a meeting of the European Community in Brussels on the 23rd of February 1978.

During the meeting the relevant members of what was essentially the EU voted to declare that a player’s nationality should not be an issue when deciding whether or not he is allowed to play football in any given county. In the summer of that year the Football League met for it’s Annual General Meeting and decided to life its de-facto ban on non-English players.

This resulted in a huge influx of talented players from outside of England entering the country to ply their trade in Blighty. Much like with Max Seeburg all those years before, it was Tottenham Hotspur that once again led the way. A double swoop for Ossie Ardiles and Ricky Villa made headlines, with the London side bringing in the two players who had just helped Argentina beat the Netherlands in the World Cup final to England.

Incidentally, it will be interesting to see how the Football Association responds to the decision of British voters to leave the European Union. Will they use that as an excuse to limit the number of foreign players entering the country to play in the Premier League and lower divisions?

Foreign Imports Limiting English Players’ Chances

Ever since 1978 there’s no question that the number of foreign players playing in England has increased exponentially. Significant events such as the Bosman Ruling in 1995 have gone on to further complicate matters, allowing players to run their contracts down and move to whichever country they like that is paying the most money. Since the invention of the Premier League in 1992 that has almost always been England, with top clubs paying large amounts of money to secure the signatures of the world’s top talents.

Critics of the free-flowing number of foreign players coming into England have claimed that it has hampered the ability of home-grown players to make it at the top level. This in turn, they say, has stopped the England national side from doing well at international tournaments. Yet is there actually any truth in that?

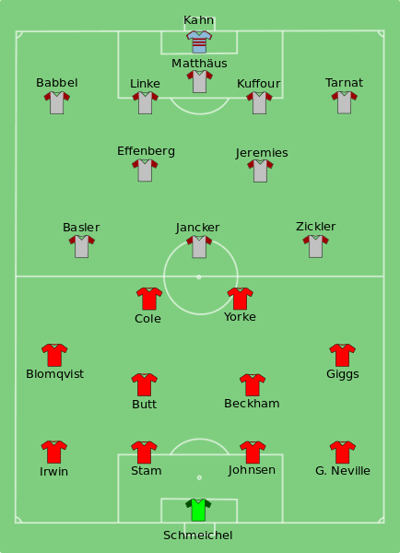

The best club competition in football is the Champions League. In 1999 Manchester United won it against Bayern Munich. The Red Devils’ starting XI featured Gary Neville, David Beckham, Nicky Butt and Andy Cole. Teddy Sheringham came off the bench in the second-half and score the equalising goal. The Bayern Munich side, meanwhile, was made up entirely of Germans with the exception of Samuel Kuffour and a substitute appearance from Hasan Salihamidžić.

Those English players also won multiple Premier League winners’ medals whilst playing under Alex Ferguson at Old Trafford. Their success wasn’t hampered by the likes of Jaap Stam and Jesper Blomqvist appearing in the team. Manchester United won the Champions League again nine years later with Wes Brown and Rio Ferdinand in the defence, Owen Hargreaves, Paul Scholes and Michael Carrick in midfield and Wayne Rooney leading the attack. They won the game playing against Chelsea, another English side.

Three years earlier Liverpool had won the Champions League against AC Milan in spectacular fashion with Steven Gerrard as their captain and Jamie Carragher in the centre of defence. Two years later Liverpool returned to the Champions League final with the same two players joined by Jermaine Pennant on the wing and Peter Crouch on the bench. In the intervening years Arsenal lost to Barcelona with a team featuring Sol Campbell and Ashley Cole.

None of that is definitive, of course, but the point is that a large number of foreign players didn’t stop the best English players making it into the starting XI of the country’s top sides. Those same sides dominated the world’s premier club competition for about a decade. Obviously foreign players were part of the English teams playing in them but so were the likes of Steven Gerrard, Frank Lampard and John Terry. All of them played for England during the same period.

The National Side

The theory that foreign imports have damaged the national side’s chances at major tournaments isn’t disproved by the fact that English clubs have made it the finals of the Champions League with English players in them. In fact, for critics of the number of non-English players in the top-flight it’s a sign that the domestic game has been strengthened at the same time that the national one has been weakened.

The number of English players making a living playing football in the top-flight has diminished year on year since the invention of the Premier League, that much is true. In the 1992-1992 season there were 69 English players in the division. By 2005-2006 that had dropped to 39. It has bumped around between the 30 and 40 mark since then, dropping to as low as 31 in the 2015-2016 season.

Obviously England haven’t won a major tournament since 1966, but winning tournaments isn’t the complete sign of how well a team is doing. The largest number of English players in the top-flight in recent years was in 1993, so how did the England national team around that time?

In 1990 they made it to the semi-finals of the World Cup, whilst in 1994 they didn’t even qualify for the same competition. Their best performance in recent times came in both 2002 and 2006 when they reached the quarter-finals of the competition when it was held in Korea & Japan and Germany respectively.

When it comes to the European Championships things aren’t all that dissimilar. The country’s best performance came when England hosted the competition in 1996 and they made it to the semi-finals. In 1992, however, they failed to make it out of the group stage. They also failed to make it out of the group in 2000. In 2008 they didn’t qualify, but in 2004 and 2012 they made it the quarter-finals.

Again, none of that is conclusive but it does seem to be the case that there’s no obvious correlation between the number of non-English players in the league and the performance of the England side in national tournaments. Perhaps critics should instead look at why the Football Association appoint managers such as Roy Hodgson and Sam Allardyce, who have career win ratios of under 40%, and expect them to be able to out-perform their own numbers.