Football is one of the most talked about games in the world. If you’re a supporter of one of the biggest clubs in the United Kingdom, particularly the best-known ones in the Premier League, you can head to almost any corner of the planet with a replica shirt on and someone will start a conversation with you. It doesn’t even matter if you don’t speak the same language, football is as universal a language as the Rosetta Stone.

From tactics to transfers, refereeing decisions to managerial appointments, there’s barely a topic that isn’t being spoken about in-depth every second of every day somewhere around the globe.

Yet one of the topics that is spoken about the least is also one that has the biggest impact on a football club’s success or lack thereof – the matter of who owns it. You usually own hear about ownership if it’s controversial for some reason. That might be because the owner isn’t investing in the club properly, or it could be because they’re investing far more heavily in the playing squad than any other team in the division is able to keep up with.

If the owner is perfectly fine, however, then you simply don’t hear much discussion about it and they’re allowed to crack on with things. Isn’t it odd, though, that in a sport which is discussed more than any other, by a significantly larger amount of people, the most important faces are largely unknown? This article is a look at the owners of the UK’s biggest clubs.

To see who owns your football club see our team owners article.

What Do Football Club Owners Actually Do?

Before discussing the various club owners with any degree of specificity, it’s first important to ask what exactly it is that an owner does. There isn’t necessarily a one-size-fits-all answer to that question, of course. The man who is widely considered to be the modern day father of Liverpool Football Club, Bill Shankly, once said, “At a football club, there’s a holy trinity – the players, the manager and the supporters. Directors don’t come into it. They are only there to sign the cheques”. Yet that’s never really been true, even in the days of the great man himself. Some owners like to appoint the manager and staff and then have nothing to with the club, whilst others prefer to much more hands-on in terms of the running of the thing that they own.

In short, owners tend to fit into one of three different categories. The first is that they’re there simply to provide capital, employing others to deal with things such as the appointment of managers and coaching staff. The second category is that of an owner that wants to provide a club with a philosophical direction. An example of this sort of way of working would be Dale Vince at Forest Green Rovers. He made his money selling renewable energy and is very much an eco-warrior, instilling his club with a sense of his own moral beliefs and turning it vegan in 2015. The final category is that of an owner that does both, ploughing money into a club at the same time as steering the direction in which that club goes. There are other categories as well, obviously, but they’re the most obvious ones when you’re looking at things in broad strokes.

Perhaps the best way of thinking about a football club is that it’s like a major business that won’t really make much money. Despite all of the finances flowing around the game from the likes of television, it’s still not common for a football club to be much of a money-maker. There’s an old joke that says you can easily make £1 million from a football club; all you have to do is invest £2 million. The majority of clubs in the Premier League are fortunate if they break even over the course of a season, thanks to the necessity to invest in the infrastructure of a stadium, the hiring and firing of staff and the need to strengthen in other areas. The most important of these is on the pitch, with the old adage being true that if you don’t improve your playing squad then you’ll go backwards, not stay still. Owners are ultimately the managing directors of these big businesses, giving the go ahead to any major investment that’s necessary and paying for it out of their own pocket – most of the time.

Why Do Owners Invest In Football Clubs?

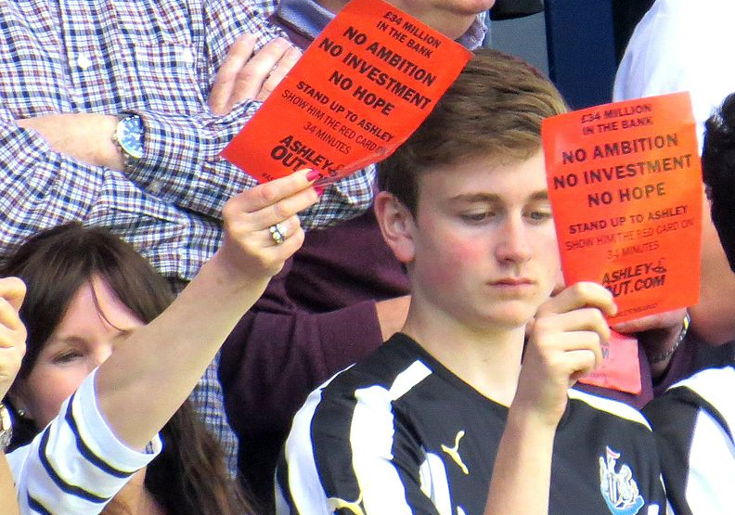

Given that it’s extremely unlikely that an owner will make much money from a football club, why do they invest in one at all? The answer to that isn’t easy to give, with each and every one having their own motivation. In some cases, such as that of Mike Ashley at Newcastle, it’s a matter of letting the heart rule the head. Ashley, who made his money through the SportsDirect franchise, was a fan of the Magpies and bought the club with the intention of taking it to the top of the sport. It ended up costing him far more than he envisioned and his ownership turned sour, with fans of the club protesting to get him to sell up whenever possible. He might well have had the best of intentions at the time, but the reality is that his ownership of the club went badly wrong very quickly and he felt as though he invested too much to cut his losses and let someone else take over the reigns.

Other examples of owning a club include the fact that sometimes good opportunities present themselves and owners can indeed end up making themselves a decent chunk of money. An example of this comes in the form of the Glazers, who currently own Manchester United. After the club went public in 2000, they gradually bought up enough shares to allow them to launch a takeover bid and, eventually, take it off the stock exchange. The problem was that they did this with loans, using the assets of the club to secure them. In other words, the Glazer family bought the club but Manchester United itself was forced to shoulder the debt that allowed them to do so. They use the club’s own profits to pay off the debts, with the long-term hope being that they’ll have a debt-free club that is worth billions. They have taken on no personal debt but could end up extraordinarily rich. Their takeover was so opposed by some supporters that it led to the launch of F.C. United of Manchester back in 2005.

Some clubs will always be appealing names for foreign investment, which could spell a tidy profit for those that own shares in them. Back in 2014 the American Stan Kroenke owned about 63% of Arsenal Football Club. Rumours emerged that a consortium from the Middle East was willing to pay around £1.5 billion for the Gunners, which would have seen Kroenke make about £400 million profit on his shares. Other owners have hoped to do similar with clubs around the country, like Vincent Tan at Cardiff City and Assem Allam at Hull City, who have both attempted to make the clubs that the own more appealing to a foreign market by rebranding them slightly. Tan felt that changing Cardiff’s kit from blue to red and playing on the Welsh dragon would make the club more interesting to the Asian market, whilst Allam thought that re-branding Hull City to make them the Hull City Tigers would be better as ‘in marketing, the shorter the name the more powerful’. Fans protested against both of them.

How Many Foreign Owners Are There In the English Leagues?

It feels as though foreign investment is becoming more and more popular when it comes to English football clubs.

Yet is that actually true? Or is it just that the most talked about owners all tend to be from foreign shores? If it is true, does it really matter all that much?

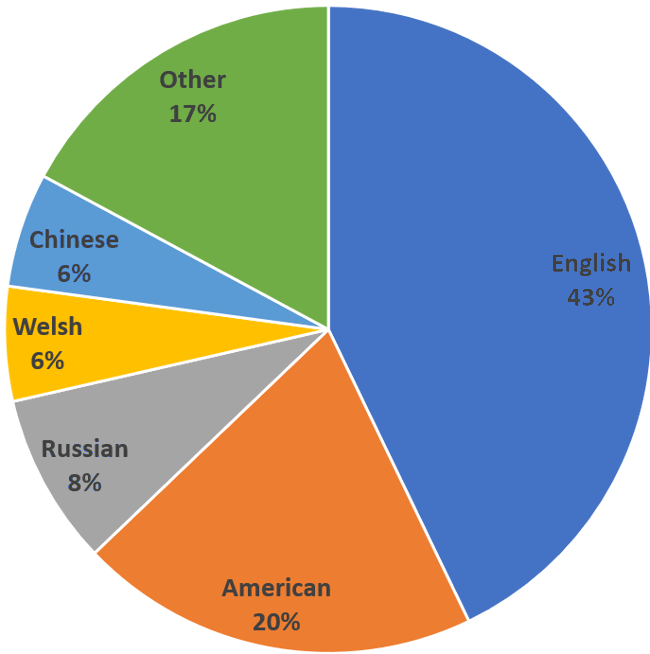

Let’s start by having a look at the country of origin of owners of Premier League clubs, then comparing that to the rest of the divisions in the Football League combined:

Premier League

Given that the Premier League is one of the most watched divisions in world football, it stands to reason that more investors in the clubs in the top-flight would come from foreign climates.

Given that the Premier League is one of the most watched divisions in world football, it stands to reason that more investors in the clubs in the top-flight would come from foreign climates.

It’s one of the richest leagues in the world and increasingly this is due to the investment of foreign money flooding into the English game.

Bearing in mind that some clubs may have more than one investor in them, here’s the current country of origin breakdown at the time of writing:

- England: 15

- USA: 7

- Russia: 3

- China: 3

- Wales: 2

- Iran: 1

- Italy: 1

- Iceland: 1

- United Arab Emirates: 1

- Thailand: 1

- Switzerland: 1

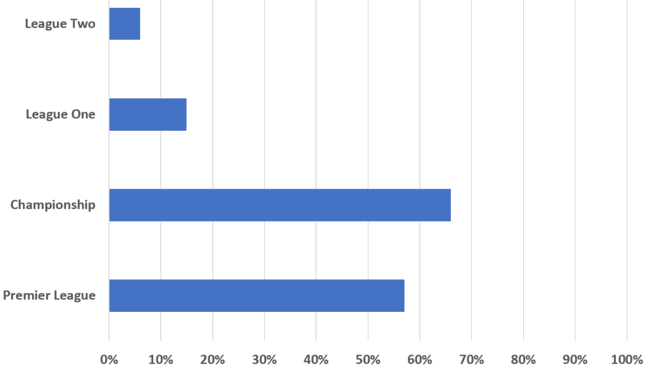

The Rest Of The Football League

It’s interesting to note that there are still more investors from England than anywhere else when it comes to looking at the Premier League, but how does the divergence in the investment look when you compare it to the rest of the Football League?

It’s interesting to note that there are still more investors from England than anywhere else when it comes to looking at the Premier League, but how does the divergence in the investment look when you compare it to the rest of the Football League?

You can see from the info below that the overwhelming majority of investment in clubs outside of the Premier League comes from England. Furthermore, twenty-nine of those sixty-two investors, or just shy of half of them, have money in League Two clubs. There are just four non-English investors in League Two clubs, compared to eight in League One and twenty-five in the Championship.

The likelihood is that those investors wanted to own a piece of the English Football League but couldn’t afford to take a stake in a Premier League Club. The Championship holds some interest because of the possibility of getting in to the top-flight, whilst that interest wanes the lower down the division that you go.

- England: 62

- USA: 7

- China: 4

- Thailand: 4

- India: 3

- Wales: 2

- Germany: 2

- Britain: 1

- Hong Kong: 1

- Pakistan: 1

- Egypt: 1

- Italy: 1

- Greece: 1

- Malaysia: 1

- Saudi Arabia: 1

- Belgium: 1

- Jordan: 1

- Scotland: 1

- Republic of Ireland: 1

- Latvia: 1

- Finland: 1

How Does Native Investment Compare With Other Major Leagues?

It’s interesting to look at how interesting other leagues around Europe are for foreign investors. Here’s a look at the number of home-grown investors compared to foreign ones in some of the top leagues:

The Scottish Premiership

We’ll start close to home, with the Scottish Premiership offering us the perfect opportunity to view a league that is close enough to England to claim something of a relationship, yet far enough removed to mean that there’s no real reason for foreign investors to spend money there if it’s an English audience that they’re hoping to spread their message to.

We’ll start close to home, with the Scottish Premiership offering us the perfect opportunity to view a league that is close enough to England to claim something of a relationship, yet far enough removed to mean that there’s no real reason for foreign investors to spend money there if it’s an English audience that they’re hoping to spread their message to.

You can see that home ownership of the best Scottish clubs is significantly more than in England’s top-flight. In fact, Tim Keyes at Dundee is the only foreign investor at the time of writing. That said, it is a little bit more complicated than that. After all, Celtic is owned by Public shareholders, whilst their fierce rivals Rangers are owned by a corporation that might well be made up of numerous different nationalities.

The fact is that the Scottish Premiership isn’t watched anywhere near as much abroad as the likes of the Premier League, making it a much less interesting investment from those outside of the country itself.

- Scotland: 11

- USA: 1

Ligue 1

Moving to the geographically next closest country, France is an interesting case when it comes to those that have invested in the country’s football clubs. Here’s a look at where they’re from in the table below.

Moving to the geographically next closest country, France is an interesting case when it comes to those that have invested in the country’s football clubs. Here’s a look at where they’re from in the table below.

Ligue 1 is obviously a much smaller division than the Premier League, but even so it’s intriguing to see the spread of nations that have invested in a French football club. Seven are from the country of the league’s origin, with the other five coming from numerous different locations.

The most fascinating is the Qatari ownership of Paris Saint-Germain, attempting to turn the French capital’s club in to a global force.

- France: 7

- Spain: 1

- USA: 1

- Russia: 1

- Qatar: 1

- Poland: 1

Serie A

The Italian league is worth a look, coming the closest to the Premier League in terms of the number of different investors from a variety of countries.

The Italian league is worth a look, coming the closest to the Premier League in terms of the number of different investors from a variety of countries.

You can see from the list that there are more Italian owners of Italian clubs than those from other nations put together. Even the six Americans on the list give a slightly false impression, given that five of them are actually part owners of the same club.

There’s enough appeal in there to attract foreign investors, but not even to make it a genuinely popular thing for them to do.

Here’s how the list breaks down:

- Italy: 12

- USA: 6

- China: 2

- Canada: 1

- Indonesia: 1

- Luxembourg: 1

La Liga

In Spain, it is common for supporters of a football club to have some form of ownership of it. Even so, there are some clubs that don’t follow those rules and have owners that aren’t the fans.

In Spain, it is common for supporters of a football club to have some form of ownership of it. Even so, there are some clubs that don’t follow those rules and have owners that aren’t the fans.

Again, there is definitely a favouritism towards Spanish owners of clubs in Spain. In fact, when you consider that the majority of fans will be from Spain and that about ten clubs in La Liga have some sort of Spanish ownership, it’s clear that foreign investors are definitely in the minority.

The fact that Spain’s two most successful clubs, Real Madrid and Barcelona, are owned by supporters tells you that it’s a method which is working.

- Spain: 15

- Fan Ownership: 10

- China: 3

- Israel: 1

- United Arab Emirates: 1

- Qatar: 1

- Singapore: 1

Bundesliga

In German football there is something called the 50+1 Rule, which dictates that more than half of every football club has to be owned by the members, or supporters, of the club. There are two exceptions to the rule, coming in the form of Bayer 04 Leverkusen and VfL Wolfsburg, the former of whom is owned by the pharmaceutical company Bayer and the latter is owned by the car maker Volkswagen. That’s because they both started out as working clubs and if a company has owned the football club for more than twenty years then they can be sole owners.

In German football there is something called the 50+1 Rule, which dictates that more than half of every football club has to be owned by the members, or supporters, of the club. There are two exceptions to the rule, coming in the form of Bayer 04 Leverkusen and VfL Wolfsburg, the former of whom is owned by the pharmaceutical company Bayer and the latter is owned by the car maker Volkswagen. That’s because they both started out as working clubs and if a company has owned the football club for more than twenty years then they can be sole owners.

Even in those two instances, things are still relatively clear; after all, both Volkswagen and Bayer are German companies, meaning that Bayer 04 Leverkusen and VfL Wolfsburg are still very much owned by the people of Germany. The most controversial club in the country at the time of writing is RB Leipzig. RB officially stands for ‘RasenBallsport’, but in reality the club is owned and operated by Red Bull. They get around the 50+1 Rule by having members, as required, but doing so in a strict manner. Membership costs are prohibitive, standing at €100 for registration and €800 annually at a time when Bayern Munich charged annual fees of between €30 and €60. On top of that, the board reserves the right to reject a membership application for no reason.

The fact that clubs have to have more than half of their shares owned by supporters doesn’t mean that individuals can’t get involved, of course. The most obvious example of a club that has outside investment is TSG 1899 Hoffenheim, which receives major financial backing from German national Dietmar Hopp. It’s interesting to note that the Bundesliga requires fans to have a say in the running of the clubs that take part in it and also boasts some of the cheapest ticket prices in Europe. That’s not a coincidence, with supporters looking after their own interests first and foremost in much the same way that millionaire investors would if they had overall control.

What Does Foreign Ownership Mean For The Future?

Now that we’ve looked at who is owning the various clubs around Europe, it’s easier to have a brief think about what all of that means for the future of teams in the Premier League. Not that there’s a definitive answer to that question, of course. People have been waiting for the financial bubble to burst in English football for years, but it shows no real sign of abating. As long as that’s the case, investment from foreign shores is likely to keep rising. It’s the popularity of England’s top-flight that makes it such an appealing thing for those from other countries, especially if they have something to sell.

English football is the most watched league in the world, with television packages worth billions of pounds. Companies that have something that they wish to let the world know about are likely to look to take advantage of this if that continues to be the case. How long will it be before Red Bull take the method that they employed with RB Leipzig in Germany and Red Bull Salzburg in Austria and attempt to do the same thing in the UK? The Austrian club used to be called SV Austria Salzburg before Red Bull bought it in 2005, so is it really so difficult to imagine the same thing being done in the Football League? Red Bull Tranmere Rovers, for example, or RB Portsmouth. They would get excellent exposure if they were able to take a club to the top of the Football League and then gain promotion to the Premier League, so it’s not that wild a suggestion.

What continued foreign investment means to the supporters of English clubs remains to be seen. As we touched on before, Bundesliga supporters pay some of the cheapest amounts for tickets to games because of the fan ownership aspect of the league’s rules, whilst English fans tend to be amongst the highest amount to see their clubs play. Protests in recent times like the walkout staged by Liverpool supporters when the club’s owners, Fenway Sports Group, attempted to raise ticket prices have made a difference, but is it enough to hold back the tide for much longer? Foreign owners have less appreciation for what a club means to the local fans, so they’re never going to be as emotionally invested as those that live and breathe the club every single day.

Moral Questions Around Foreign Investment

One of the most interesting topics of debate in recent times has surrounded the moral questions that come attached with some foreign investment. Roman Abramovich was the first billionaire to invest in a football club when he bought Chelsea from Ken Bates in 2003. Reports suggest that the Russian was the first person to make a suggestion to Boris Yeltsin that Vladimir Putin would make a worthy successor to him. There have also long been question marks surrounding the legitimacy of his wealth. As was said in The Times, “Abramovich famously emerged triumphant after the ‘aluminium wars’, in which more than 100 people are believed to have been killed in gangland feuds over control of the lucrative smelters”.

Similar question marks surround the owners of Manchester City. Sheikh Mansour is the half-brother of the Sheikh Khalifa. Sheikh Khalifa is the absolute ruler of the United Arab Emirates, which is another way of saying he’s a dictator. Nick Cohen summed it up neatly in his article for The Guardian when he wrote, “The Emirate monarchies, Qatar and Saudi Arabia rely on a system of economic exploitation you struggle to find a precedent for…But comparisons with apartheid or the Israeli occupation of the West Bank or America’s old deep south miscarry because the Arab princelings import their working class rather than rule over subdued inhabitants”.

On the whole, Neither Manchester City nor Chelsea fans have been quick to protest against their owners on moral grounds, mainly because they’ve brought success. Likewise Paris Saint-Germain have become the most successful club in France thanks to investment from Qatar, but their supports turn a blind-eye to the more problematic nature of that investment. The issue is, where do you draw the line? Chinese investment is becoming more and more common, but that’s another country that has a questionable record on human rights. There are millions of people who don’t like Donald Trump, so does American ownership cause problems as long as the former The Apprentice host remains President? Some things are worse than others, of course, but it’s an interesting conundrum that football supporters might have to wrestle with more and more in the coming years.