When football matches need to be decided on the day, the first thing that referees will do if the scores are still level after ninety minutes is to take the game to extra-time.

When football matches need to be decided on the day, the first thing that referees will do if the scores are still level after ninety minutes is to take the game to extra-time.

For the watching supporters that will either offer hope that their team will be able to pinch a victory or else dread that more time will simply tire their team’s players out and perhaps even result in their humiliation. When a match has been thrilling, the prospect of extra-time is great because it means we’ll get to watch it for longer. When the game has been awful, extra-time just seems like a punishment that nobody deserves.

Yet where did the idea of extra-time come from? Not all games during football’s more formative years will have been thrillers, so who decided that the best thing to do would be to subject everyone to another half an hour of a match? Why was half an hour chosen as the allotted time that extra-time would last?

They’re not all easy questions to answer, given that the history of football always seems to impenetrable. We’ll do our best to answer what we can here, though. Extra-time was introduced to football before penalties were created, but the fact that spot kicks came along suggests not everyone was a fan.

The Early Days Of The Rules

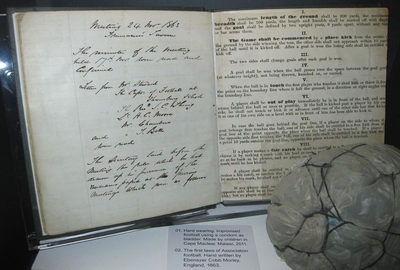

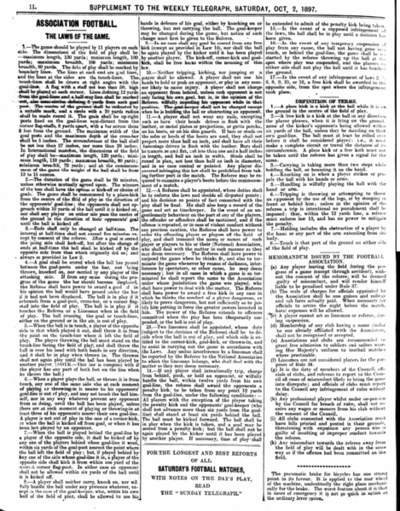

When the Football Association sat down to write its rules of the game in 1897, one of the things that was enshrined into how matches would be settled was extra-time. Given that the first rules were written in 1863, mind, that suggests that there was no easily determinable outcome for football games before that, even if an outcome was a necessity.

Of course, there wasn’t much of a need to worry about that in 1863 when you consider that there was also no provision regarding how long a match should last for and half-time hadn’t been introduced yet. Indeed, the various different Associations around the country used their own rules prior to the introduction and implementation of the International Football Association Board.

With the Sheffield Football Association deciding to come on board with the national Football Association in 1877, the need to have more concrete rules for virtually every aspect of the game became evident. For that reason changes were made in 1897 that would alter the way that football was played forever.

The 1897 Rules

The rule changes introduced in 1897 might seem basic in some ways, but in reality they were revolutionary in the manner in which they clarified certain aspects of the game of football. For the first time since the sport had come into existence, it was specified exactly how many players could play on each team – 11.

Far more importantly as far as this piece is concerned was the fact that the duration of each match was enshrined in law as being 90 minutes. The only time that would be different was if it had been decided upon beforehand. Even then it wasn’t locked in in terms of being a globally accepted thing.

As an example, the 1922 German Championship final saw Hamburg and Nuremburg tied after ninety minutes, so they essentially played out the match like the childhood game of ‘next goal wins’, with nobody scoring after another 99 minutes of play and the encroachment of dusk meaning that the game needed to be abandoned.

30 Minutes Became The Norm

Slowly but surely, playing extra-time as an additional 30 minutes simply became the accepted norm in world football.

Slowly but surely, playing extra-time as an additional 30 minutes simply became the accepted norm in world football.

If things still couldn’t be decided after that then a replay would be in order and if another 120 minutes was unable to separate the two teams then a match would be decided by the fortune of a coin toss.

In 1968 the semi-final of the European Championship between Italy and the Soviet Union was decided thanks to Giacinto Facchetti correctly calling the toss of a coin, which was the only time in history that a Euro or World Cup game had to be decided in such a manner.

Given the importance of the game, it was decided that a better system needed to be found.

It Remained Confusing For Many

That ‘better system’ turned out to be the penalty shootout, which was enshrined into footballing law by IFAB by 1970. Not that the international body had made clear to everyone how it should work.

Rangers became the unwitting victims of this sense of confusion in the Second Round of the 1971-1972 European Cup Winners’ Cup when they scored in extra-time to take the game to 6-6, thinking they’d win by away goals. Instead the referee ordered a penalty shootout and Sporting Lisbon won instead.

Whilst the Rangers players sat disconsolate in the dressing room, a journalist that they knew arrived to inform them that there were through to the next round on away goals thanks to Willie Henderson’s extra-time strike. It led to Rangers eventually winning the Cup Winners’ Cup, which is their only European trophy to date.

It certainly demonstrated the manner in which extra-time might have been made into footballing law but still wasn’t quite understood by everyone.

Variations On A Theme

It doesn’t take much for FIFA to decide to meddle with the way football works, so the 1990s saw the organisation try to do something clever with extra-time. Rather than simply allowing it to play out the way it always had, the governing body introduced the idea of the ‘Golden Goal‘. It was essentially a sudden death scenario, in which the first team to score a goal in extra-time would automatically win, with FIFA’s hope being that it would encourage more attacking play.

Introduced in 1993, it was influential in how Germany won Euro ’96, when Oliver Bierhoff’s deflected shot caused the Czech goalkeeper Petr Kouba trouble and the Germans won their third title as a result. On a club level, it was Liverpool in 2001 that were the benefactors of the new rule, completing an historic treble thanks to a Golden Goal in extra-time during their UEFA Cup game against Alaves that saw them finish the match as 5-4 victors.

It didn’t last long before FIFA began to reconsider the rule. The fear of conceding a killer goal meant that it actually resulted in less attacking play rather than more. The next plan was to have a Silver Goal, which meant that if a team scored first then the opposition would have until the end of the half to respond and if they failed then they would lose. That lasted until 2004, at which point the traditional 30 minutes of extra-time prior to penalties was once again made the norm.

The Psychology Of Extra-Time

These variations on the same theme proved both that extra-time wasn’t seen as the best way of settling a match by most people, as well as the fact that there weren’t really any better ones available. For the teams taking part in matches that boast extra-time, it’s really just a test of which one of them is the fittest. A side that is able to keep playing for 120 minutes is more likely to win the game in extra-time than one that is looking exhausted after the normal 90 minutes of play. Should fitness really be the deciding factor in a match?

According to Dr John Sullivan, who works as a sports psychologist, the pressure of extra-time can be ‘overwhelming’ for footballers who will start to be overtaken by ’emotion and fatigue’. Kouba, the Czech Republic’s goalkeeper who conceded the Golden Goal in 1996, believes that players also start thinking about the likelihood of extra-time when there’s still plenty of normal time still to play. ‘It’s about risk management’, he said.

The psychology can work in one team’s favour, such as when Sir Alf Ramsey told his England players that the West German players were ‘finished’ after 90 minutes when they were lying on the turf before the start of extra-time. ‘”ou’ve won it once”, he said. “Now go and win it again”. They thought it was all over…and then it was. Given that the likes of the World Cup and the European Championship can result in every match after the Group Stage going to extra-time, it’s vitally important for participants to master physical and psychology recovery from their extra-time exploits.

Is Extra-Time’s Future Likely To Be Limited?

In the summer of 2018, the English Football League confirmed that it would be scrapping extra-time in the EFL Cup. If matches weren’t decided after 90 minutes then there would be no period of extra-time and instead games would just go straight to a penalty shootout. The rule was put in place for the 2018-2019 season after clubs voted to get rid of the extra thirty minutes of play. It was seen as unhelpful for teams taking part in English football’s third trophy, with the hope being that removing extra-time would reduce the chance of fatigue for the players.

In the summer of 2018, the English Football League confirmed that it would be scrapping extra-time in the EFL Cup. If matches weren’t decided after 90 minutes then there would be no period of extra-time and instead games would just go straight to a penalty shootout. The rule was put in place for the 2018-2019 season after clubs voted to get rid of the extra thirty minutes of play. It was seen as unhelpful for teams taking part in English football’s third trophy, with the hope being that removing extra-time would reduce the chance of fatigue for the players.

During the same summer, UEFA confirmed that teams would be able to make a fourth substitution during the period of extra-time in the Champions League and the Europa League. This was also designed to reduce the chance of fatigue, with managers able to make all three standard subs during the 90 minutes of the match safe in the knowledge that they could make one more change during extra-time rather than having to hold one of the three subs back during the match just in case things were undecided after the 90. It followed a move from the FA doing the same thing two years earlier.

The various moves being made by governing bodies around the world suggest that there’s an appetite to find a fairer way of doing things than extra-time allows. Let’s say that one team in the World Cup won their semi-final match in 90 minutes and the other needed extra-time to get through to the final. Let’s also imagine that the team that didn’t need to play extra-time also played the day before the one that did. That means that they not only had an extra day’s rest but also played 30 minutes less football than their opposition in order to get to the final.

You’re then in a situation where the World Cup final, the culmination of world football’s showpiece event, isn’t about which team is better but is about which one has played less football. Is that right? Should that be the thing that decides such a prestigious match?

It’s notable that in both the Copa America and the Copa Libertadores the only stage of the competition that features extra-time is the final. That removes the chance of one team having an unfair advantage over another because they had to play extra-time in a previous round. Shortening extra-time could be an option, too. It would potentially lead to teams being more attacking if they’ve got less time to worry about fatigue kicking in.

Interestingly, Four Four Two magazine notes that before penalty shootouts were introduced, when drawn matches would be decided by the fate of a coin toss, 94% of matches finishes inside 120 minutes as teams feared losing out by the fate of the toss of a coin. Since penalties came in and weaker teams could cling to the ‘lottery’ of that way of winning a game, that has shifted down to 78%.

Perhaps, then, it isn’t extra-time that’s the problem but rather the manner in which matches are settled if extra-time doesn’t produce a winner? Gerard Houllier, the Liverpool manager when they won the UEFA Cup in 2001, says on the matter of extra-time, “If you find a better system, let me know”. Football’s governing bodies continue their search.