In August of 2019 Bury Football Club was expelled from the English Football League after the club failed to agree a takeover deal and couldn’t meet its financial obligations.

It came at the same time as Bolton Wanderers were struggling to pay players and staff, but the EFL gave them an extension to the deadline they’d been given as they were in the process of agreeing a takeover with Football Ventures (Whites) Limited, which eventually went through and helped the club avoid a similar fate to Bury.

It was a cruel fate for the club and its fans. They had only earned promotion to League One four months before, yet their financial troubles had pre-dated that. Players hadn’t been paid in November of 2018, with Stewart Day eventually agreeing to sell the club to Steve Dale for just £1.

More problems arose for the club in the months that followed, even whilst things were going well on the pitch. Former Bury player Ryan Lowe had been made manager and took them to the edge of promotion at the same time as Her Majesty’s Revenue & Customs issued the club with a winding up order. Football fans couldn’t help but ask, how did it come to this?

The History Of Bury FC

The football club in the Bury area of Greater Manchester was founded in 1885 when a local football enthusiast named Aiden Arrowesmith organised meetings between the two local church teams of Bury Wesleyans and Bury Unitarians.

Immediately the two sides agreed that any new team should be professional, despite the fact that the idea of doing so remained controversial at the time. Soon the new club leased some land from the Earl of Derby’s estate at nearby Gigg Lane, playing a friendly there against a team from Wigan on the 12th of September 1885.

When the Lancashire League was formed in 1889 Bury were founding members of it, finishing the first season in second place. They went on to win the competition for the following two seasons, winning the Lancashire Cup for the first time in 1892. When they played Everton in the cup final that year the club’s manager, who was also the chairman, told his players that they’d ‘shake ‘em’, earning the club its nickname of ‘The Shakers’.

The club continued to enjoy some success over the years that followed before being elected to the Football League in 1894.

Bury Make The Top-Flight

In the 1894-1895 season, which was Bury’s first in the Second Division, the club won the title by 9 points, earning a place in the test match against the First Division’s bottom club to see which side would play in the top-flight the following season.

Bury beat a relatively new side called Liverpool, which had only been formed a few years before. They remained in the top-flight for the following 17 seasons, eventually being relegated back to the Second Division in 1912.

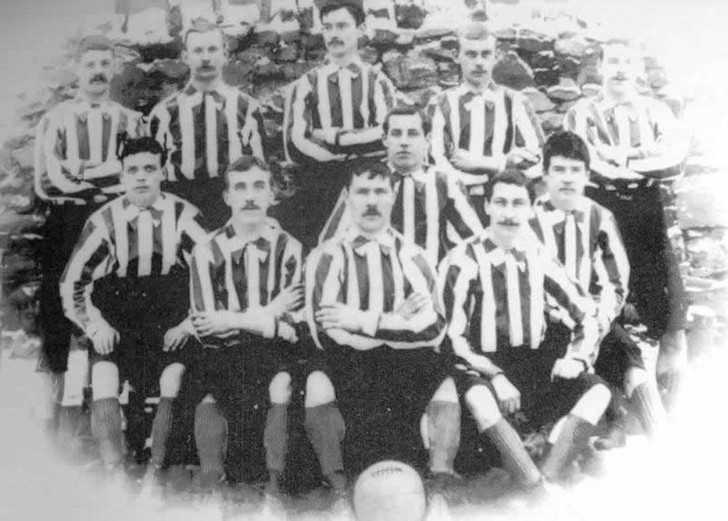

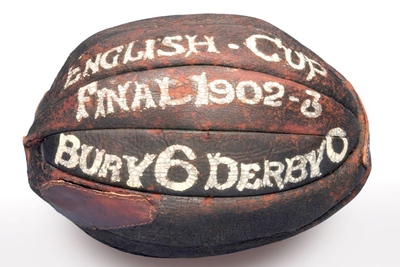

Their time in the top-flight was punctuated with two FA Cup wins in 1900 and 1903, being drawn away from home in every round of their 1900 run to the final before beating Southampton 4-0 in the final. Their journey to the final in 1903 was equally as noteworthy because they didn’t concede a goal in any round.

They played the likes of Wolverhampton Wanderers, Sheffield United and Aston Villa on their way to the final against Derby. Because the two clubs had identical coloured kits they agreed to play in the kits of different teams.

Then Bounced Between Divisions

In the decades that followed, Bury essentially cemented their position in the Second Division, though they came close to gaining promotion back to the top-flight in the post-Second World War years.

They were nearly relegated out of the second-tier a few times in the 1950s, finally dropping out in 1957. They returned at the end of the 1960-1961 season and stayed there for six out of the next seven campaigns. As the 1960s rolled into the 1970s the club bounced around between the top three flights of English football before finally being relegated to the Fourth Division in 1971.

The club struggled for a long time after that, only really getting a run of results together when Stan Ternent was made manager. He secured successive promotions during the 1990s, winning the Division Two title in 1997.

That was the third-tier of the Football League by that point, thanks to the advent of the Premier League, which meant that the club was back in the second-tier for the first time since the 1960s. They were relegated back down at the end of the season in cruel circumstances, but far worse was to come.

The Club’s Financial Woes Begin

During the 2001-2002 campaign ITV Digital collapsed, causing clubs in the lower leagues of English football no end of problems. For Bury, the collapse took them into administration and close to having to fold altogether. It was only thanks to a campaign by supporters that they were able to raise enough money to stay afloat.

During the 2001-2002 campaign ITV Digital collapsed, causing clubs in the lower leagues of English football no end of problems. For Bury, the collapse took them into administration and close to having to fold altogether. It was only thanks to a campaign by supporters that they were able to raise enough money to stay afloat.

It wasn’t enough to stop the problems on the pitch, though, and the club was relegated back to Division Three at the end of the season. Whilst the club was able to sort out its financial mess in the years that followed, it was never far away from being in trouble.

In 2012, for example, the club was hit with a transfer embargo after poor attendance figures led to financial problems. Stewart Day took over the club in 2013 and paid around £1.5 million to remove debt, with the team doing better on the pitch and eventually earning promotion back to League One. They returned to League Two at the end of the 2017-2018 campaign, then won promotion back up again at the end of the following season thanks to fourteen successive matches without losing.

When Steve Dale bought the club in December of 2018 he paid an outstanding tax bill to HMRC in order to avoid a winding up order, but by April of 2019 the problems had resurfaced.

Expulsion From The Football League

Steve Dale confessed in April of 2019 that the club’s financial issues were far worse than he realised when he’d taken over. In order to try to avoid the club hitting major issues he suggested that a Company Voluntary Arrangement might be the way forward, paying off the club’s creditors and paying 25% of monies owed to the likes of HMRC.

Steve Dale confessed in April of 2019 that the club’s financial issues were far worse than he realised when he’d taken over. In order to try to avoid the club hitting major issues he suggested that a Company Voluntary Arrangement might be the way forward, paying off the club’s creditors and paying 25% of monies owed to the likes of HMRC.

Because the EFL considers a CVA to be an insolvency event, the club was threatened with a 12 point deduction before the season had begun. In July the EFL then sought further reassurances about how the club would even be able to satisfy the EVA, which wasn’t provided.

The result was that the club’s opening fixtures were suspended. Eventually the EFL informed Bury that they had 14 days to provide them with plans regarding how debt would be paid off, with Dale rejecting an offer to buy the club because he believed that he could get more money.

The EFL offered a 48 hour extension to the expulsion deadline when it emerged that four parties were interested in buying the club, however C&N Sporting Risk pulled out of a deal just an hour before the deadline and at 11pm on the 27th of August 2019 the EFL released a statement confirming that the club had been expelled from the Football League, becoming the first to suffer the fate since Maidstone United in 1992.

How Was It Allowed To Happen?

Modern football is seemingly awash with money. On the same day as Bury’s fate was being sealed, Manchester United agreed a loan move for Alexis Sanchez to head to Inter Milan, confirming that they would be paying some of his £350,000 per week wages at the same time.

The natural question, then, is how this was ever allowed to happen. The answer in part lies in the fact that there are rules that stop clubs in other divisions from helping out teams in financial trouble. There are also serious questions to be asked over the Football League’s ‘fit and proper person’ test, which is supposed to stop people without the financial means or wherewithal from taking over clubs and then allowing them to suffer the consequences.

Players complained over the manner in which Dale was running the club, with Jill Neville resigning as Secretary and a former director, Joy Hart, chaining herself to the railings of the club in protest at his ownership. That is suggestive of a person who was never fit and proper, yet the EFL abdicated all responsibility for Bury’s demise and simply said that it was ‘one of the darkest days’ for the organisation before making a reference to the ‘football family’.

There might be plenty of money in football, but if a club isn’t run properly and the people in charge are more interested in turning a profit than protecting a club’s history then there’s not much anyone can do to send that money to the right places.

What Will Happen To Gigg Lane?

Gigg Lane opened its doors for the first time in 1885 when it was little more than just a field in Bury. Once large enough to fit 35,000 supporters through its doors, the club never registered a league crowd smaller than 1,000 people at the stadium.

It has enjoyed numerous sponsors over the years, becoming the JD Stadium in 2013 thanks to a deal between the club and JD Sport. In February of 2019 it was announced that a deal had been made with Leeds-based Planet-U Energy to take over sponsorship responsibilities, with the stadium being powered completely by renewable energy.

What will happen to both that deal and the stadium itself will depend largely on what happens to the club. Many believe that liquidation is almost certainly going to be the next step, with expulsion from the Football League likely to mean that no money can be made from gate receipts and it will no longer be a trading business.

The players contracted to the club are free to leave, as are the academy players. The club’s ground, meanwhile, is mortgaged to a company called Capital Bridging Finance Solutions for £3.7 million. Bury Council has said that it is ’protected for sporting purposes’, so even if they took ownership of it they would be unable to develop it.

In the past local teams such as Manchester United and Bolton Wanderers have used the ground to host reserve team matches, so it’s possible that they will look to do the same thing moving forward. It has also hosted other sporting events in the past, including rugby league matches, baseball, cricket and lacrosse. Should Bury supporters be able to launch a new club from the ashes of the former one then there’s no question that they’d be keen to play matches are the side’s historic home, but right now that looks a long way away from happening.